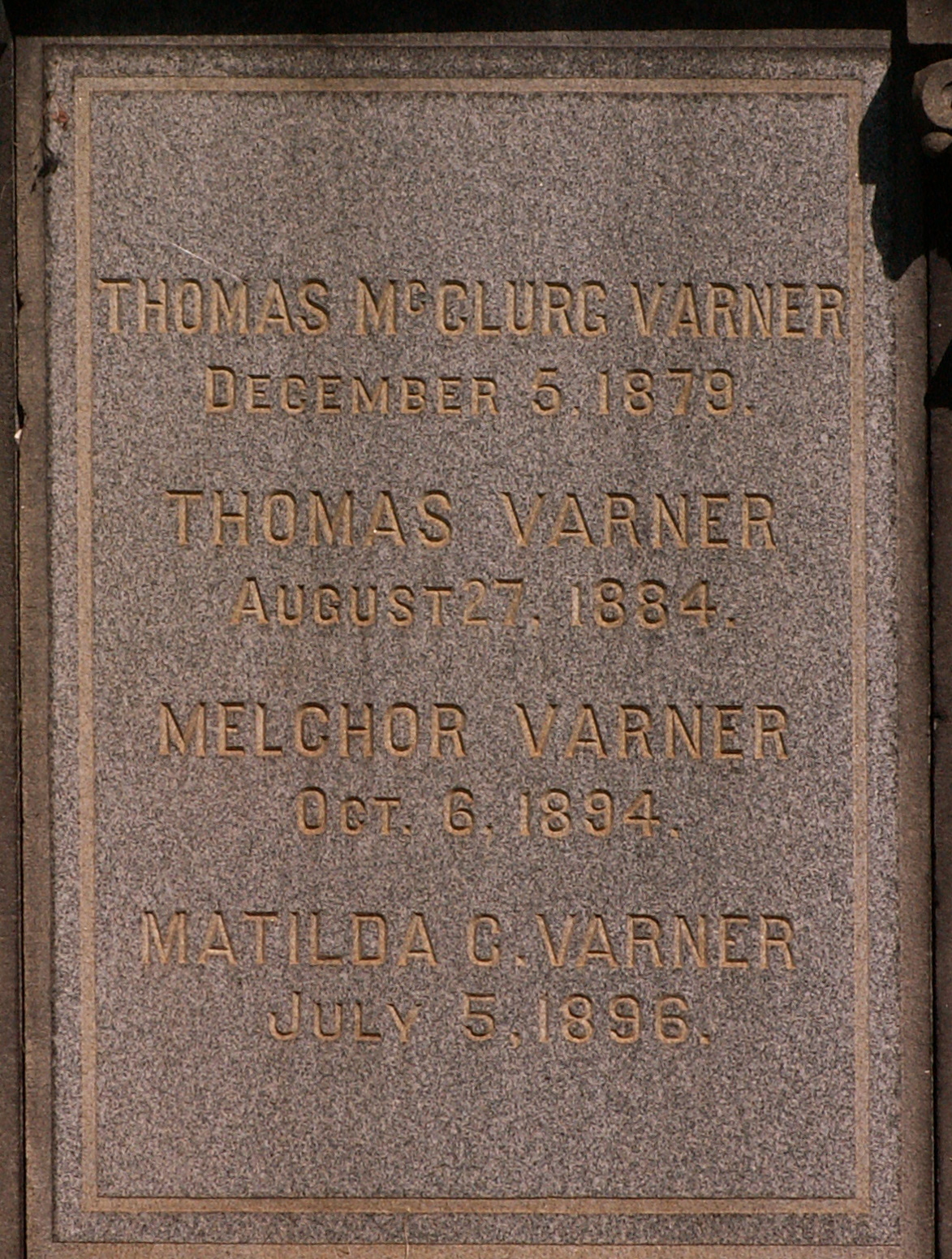

This imposing Corinthian monument has stories to tell, and perhaps someone with more time than old Pa Pitt has on his hands will follow the hints and fill in the tales. The statue on top is of Thomas McClurg Varner, only son of Melchor Varner and his wife Matilda (McClurg) Varner; he died in 1879 when he was only nine years old. (Childhood mortality in the 1800s was worse among the poor, but it did not spare even the very rich.) The boy was probably named for Thomas McClurg, Matilda’s very rich father (he seems to have owned the land that is now the South Side), who died when Matilda was young, leaving his children a large inheritance.

This imposing Corinthian monument has stories to tell, and perhaps someone with more time than old Pa Pitt has on his hands will follow the hints and fill in the tales. The statue on top is of Thomas McClurg Varner, only son of Melchor Varner and his wife Matilda (McClurg) Varner; he died in 1879 when he was only nine years old. (Childhood mortality in the 1800s was worse among the poor, but it did not spare even the very rich.) The boy was probably named for Thomas McClurg, Matilda’s very rich father (he seems to have owned the land that is now the South Side), who died when Matilda was young, leaving his children a large inheritance.

Matilda also had a brother named Thomas, after his father, who died when his nephew Thomas was very young, leaving a large inheritance to his sister “for her sole and separate use, and so that her said husband shall not have any control over or use of the same.” This suggests a fascinating story of family feuding, and perhaps a marriage that was considered unwise by Matilda’s family. It seems that Matilda was not happy with the conditions imposed on her use of the inheritance. Litigation on the younger Thomas’s will went all the way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, whose 1875 decision was apparently considered an important precedent in the law of trusts.

Matilda also had a brother named Thomas, after his father, who died when his nephew Thomas was very young, leaving a large inheritance to his sister “for her sole and separate use, and so that her said husband shall not have any control over or use of the same.” This suggests a fascinating story of family feuding, and perhaps a marriage that was considered unwise by Matilda’s family. It seems that Matilda was not happy with the conditions imposed on her use of the inheritance. Litigation on the younger Thomas’s will went all the way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, whose 1875 decision was apparently considered an important precedent in the law of trusts.

That decision was not the end of the story, however: ten years later, in 1885, we find the Pennsylvania General Assembly approving the second version of an act to set aside the trusts arising from the will of Thomas McClurg; or, in other words, to set aside that one decision of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. (The first version of the act apparently was incorrectly worded and therefore unconstitutional.)

Whatever tensions there may have been between Varners and McClurgs, the Varner family stayed together: Melchor and Matilda are buried here with their son, and another Thomas Varner—probably Melchor’s father of that name.

With these hints and references, someone interested in South Side history should be able to do a little historical detective work and fill in the rest of the story. And if anyone who does so will leave some of the information in the comments, Father Pitt will be very grateful.