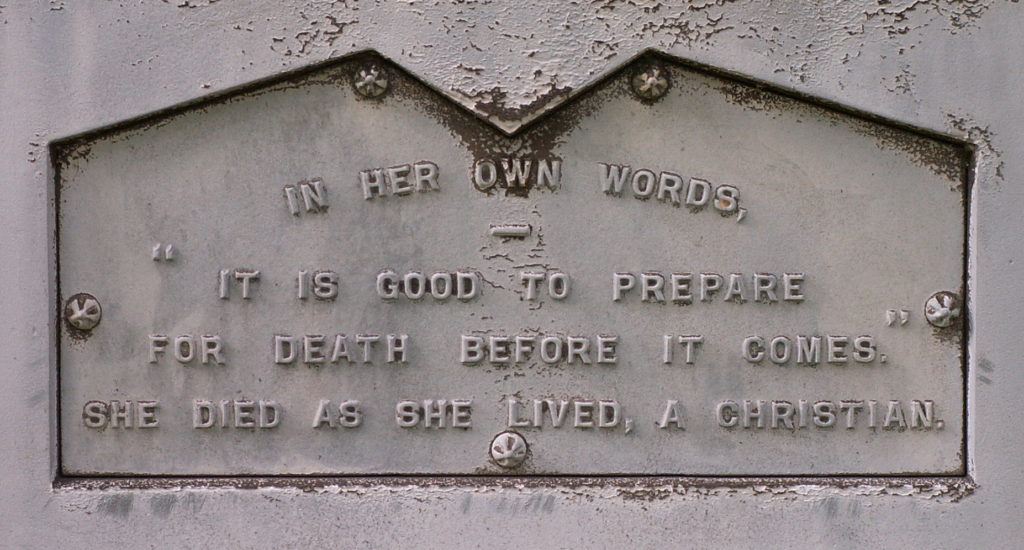

Zinc monuments like this were cheap substitutes for stone; they were sold as “white bronze” by the monument dealers. High-class cemeteries considered them vulgar and often prohibited them outright, as apparently the Allegheny Cemetery did; but somehow some families managed to sneak them in anyway. As it turns out, they last better than the expensive marble from which many of the best monuments were made. They were constructed from interchangeable parts, so that one could choose from a huge variety of symbols, epitaphs, canned rhymes, and Bible verses to be included in the monument, and the manufacturer would oblige simply by screwing in the proper plates. Custom inscriptions were also much cheaper to make by stamping letters in standard plates than by cutting them in stone.

Here is a particularly spledid zinc monument, nine feet tall, festooned with as many slogans and symbols as the bereaved husband could afford. In spite of a clumsy restoration attempt—never, never restore a zinc monument with concrete, the Smithsonan warns—it is overall in excellent condition after 134 years or so.

In front are two little zinc headstones for “Mother” and “Father.”